Twórczość Tomasha Fugiel w sposób świadomy wykorzystuje nowoczesne techniki (digital painting). Abstrakcyjne, nietytułowane kompozycje otwierają pole interpretacji, sieć skojarzeń warunkowanych osobistym gustem, preferencjami estetycznymi, ale także różnorodnymi konotacjami kulturowymi. I owe kulturowe asocjacje wydają się być i zamierzone przez Artystę, i najciekawsze w odczytaniu-odczytywaniu Jego twórczości.

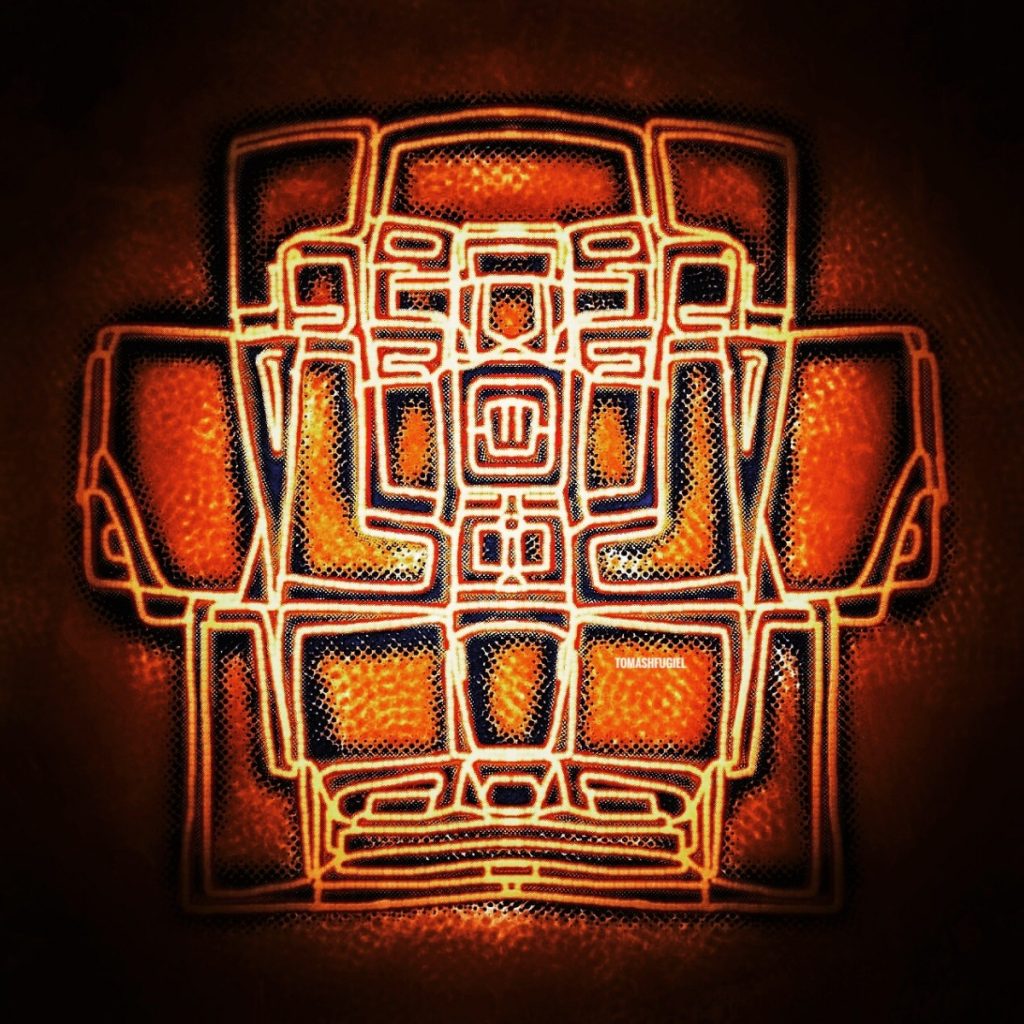

Narzucające się jest wrażenie harmonii, jakie Jego prace wywołują. Centralna kompozycja, wertykalna oś symetrii, stabilne, matematycznie wyznaczone proporcje dają im uporządkowanie; powtarzające się elementy (koła, elipsy, łagodne łuki, kwadraty) – rytm. To wrażenie wzmacnia kolorystyczna organizacja kompozycji: czysta, świeża kolorystyka; monochromatyczne tło, w większości prac zróżnicowane walorowo, „rozświetlone”, kieruje wzrok ku centrum.

Światło, blask, claritas – średniowieczny synonim piękna, plotyński znak transcendencji przeświecającej przez to, co zmysłowo dane. Materia jest ciemnością, duch – światłem, a sztuka powinna wyjść poza materię i pokazać ducha. To, co estetyczne (w podwójnym znaczeniu tego terminu) jest formą dostępu do tego, co poza powierzchnią. Światło wydaje się mieć istotne znaczenie dla Artysty, jego refleksy pojawiają się bowiem we wszystkich pracach, także wewnątrz kompozycji. To sprawia, że „centrum” staje się rozproszone, zwielokrotnione, w istocie niedostępne.

Forma prac swobodnie nawiązuje do mandali z jej złożoną symboliką: koła – harmonii, doskonałości, nieskończoności, zewnętrzności i kwadratu – człowieka, ziemi, czterech stron świata, które łączy centralny punkt. Reinterpretacja Tomasha Fugiel mandalę rozbija – mamy prace z dominującą strukturą kwadratu, w innych pozostaje koło… Jung w mandali widział odbicie naszej jaźni, całości psychiki – tu mamy obraz jaźni, której spójność uległa załamaniu.

W wielu obrazach Artysta przełamuje pierwsze wrażenie spokoju i harmonii zagęszczając, nakładając na siebie powielające się motywy, meandrycznie prowadząc linię o organicznej formie wprowadza niepokój w pozornie prostą, czytelną konstrukcję. Dekonstruuje pojęcia centrum i źródła, uprzywilejowanego punktu odniesienia dając wizualną metaforę kłącza.

Abstrakcyjne kompozycje można odczytywać antropomorficznie – po części to ironiczne nawiązywanie do kultury popularnej, po części do kultury Azteków dające twarze – maski, sylwetki – totemy; czasem nieostre, rozmyte, nie wiadomo, czy w trakcie kształtowania, czy przeciwnie, rozsypujące się. Ta ambiwalencja, charakterystyczna dla sposobu obrazowania Tomasha Fugiel szczególnie widoczna jest w jednej z prac: można w niej widzieć postać jakiegoś wielorękiego wschodniego bóstwa, można także swoistą interpretację motywu „człowieka witruwiańskiego” Leonardada Vinci. Swoistą, bowiem relację Kosmos – mikrokosmos, proporcje odpowiadające doskonałym figurom geometrycznym zastępuje tu struktura amorficzna, miękka, wpisana w sieć (Chaos – mikro-chaos?).

Koronkowa, biżuteryjna forma części prac przywołuje obrazy planów średniowiecznych kościołów – przestrzeni oddającej ducha scholastycznych traktatów. Takich tropów w twórczości Artysty pojawia się więcej; to sztuka budowana jak palimpset: własny tekst nakłada na teksty kultury już skodyfikowane, obrosłe interpretacjami stając się – jak każde dzieło sztuki według Umberto Eco „… przekazem z istoty swej nieokreślonym, wielokrotnością znaczeń”.

Tomash Fugiel work uses modern digital painting techniques in a conscious way. Abstract, untitled compositions open to interpretation, a network of associations conditioned by personal tastes, aesthetic preferences, but also diverse cultural associations. These cultural associations seem to be intended by the Artist, and most interesting in reading his works.

The impression of harmony that his works bring is overwhelming. The central composition, the vertical axis of symmetry, the stable mathematical proportions provide order; repetitive elements (circles, ellipses, smooth arches, squares) – lend rhythm. This impression is enhanced by the color organization of the composition: clean, fresh coloring; monochrome background, qualitatively varied in most of the works, „illuminated” – directs the eye toward the center.

Light, brilliance, claritas – the medieval synonym of beauty, the platonic sign of transcendence through what is given sensually. Matter is darkness, spirit – light, and art should go beyond matter and show the spirit. That which is aesthetic (within the double meaning of this term) is a form of access to what is beyond the surface. Light seems to be of large significance to the artist, as its reflections appear in all the works, also within the composition. This makes the „center” scattered, multiplied, in fact inaccessible. The form of work is loosely reminiscent of the mandala with its complex symbolism: the circle – harmony, perfection, infinity, outwardness and the square – man, earth, the four corners of the world, connected at the central point. Tomash Fugiel reinterpretation breaks the mandala up – we have works with the dominant square structure, others are based on the circle … Jung saw the reflection of our ego in the mandala, the whole of the psyche – here we have an image of the self, whose cohesion has collapsed.

In many of his paintings, the Artist breaches the first impression of peace and harmony by densifying, overlapping, multiplying motifs; by means of meandering, organic line, he introduces anxiety into a seemingly simple, clear construction. He deconstructs the concept of center and source, a privileged reference point, giving a visual metaphor of a rhizome.

Abstract compositions can be read anthropomorphically – in part as ironic references to popular culture, partly to Aztec culture with its faces – masks, silhouettes – totems; sometimes blurry, fuzzy, uncertain as to whether being in the course of shaping or on the contrary, scattering. This ambivalence, characteristic of Tomash Fugiel imaging, is particularly evident in one of the works: one may see within it the form of a many-armed Eastern deity, or a specific interpretation of the Leonardo da Vinci’s motif of the „Vitruvian man”. Specific, because the Cosmos-microcosm, proportions corresponding to perfect geometric figures, are replaced here by an amorphous, soft, networked structure (Chaos – micro-chaos?).

The lacy, jewelry-like form of some works evokes construction plans of medieval churches – a space reflecting the spirit of scholastic treatises. There are more such traces in the Artist’s work; it’s art that is built like a palimpsest: its own text is superimposed on cultural texts already codified, interwoven with interpretations, becoming – like any work of art, according to Umberto Eco „… a message from the essence of its undefined, multiple meanings.”